Studying Pregnancy Safely: Observational Research Explained

Contrary to what headlines and social media often suggest, science doesn’t actually deal in proof; it deals in probabilities. Studies give us estimates of how the world likely works, not absolute certainty – and the stronger their design and execution, the closer those estimates get to the truth.

Why do we accept some health claims as fact (e.g., smoking causes lung cancer, Accutane causes birth defects), while other associations remain much more contested (e.g., Does moderate red wine consumption improve or harm heart health? Does Tylenol cause autism?)?

The difference often comes down to the strength of the evidence behind each claim: how studies are designed and what shapes the conclusions we can draw.

In Part I of our blog series about observational research, Why Don't We Know More About Pregnancy?, we covered how the history of women’s inclusion in health research – from pregnancy tests using barley seeds in ancient Egypt, to the thalidomide tragedy, to FDA-mandated rigorous studies – has shaped pregnancy research practices and the evidence we rely on today.

In Part II, we dive into the fundamentals of how scientific evidence is built in pregnancy as we continue to evolve the evidence base. This foundation helps explain both how to recognize which claims deserve confidence today, as well as how we can build stronger evidence where gaps currently exist.

The scientific method: The foundation on which new knowledge is built

The scientific method – the process of systematically acquiring new knowledge from observed data rather than just theory or logic – aims to get at what is true about the real world. Contrary to what headlines and social media often suggest, science doesn’t actually deal in proof; it deals in probabilities. Studies give us estimates of how the world likely works, not absolute certainty – and the stronger their design and execution, the closer those estimates get to the truth.

How do researchers actually apply this? They start with a research question, which often aims to understand a causal relationship (e.g., Does Accutane cause birth defects?). You then generate a testable hypothesis (“The risk of birth defects is higher among babies exposed to Accutane compared to babies not exposed”), collect data (about moms and babies who are exposed, and who are not exposed), analyze it, and draw conclusions based on the data.

The challenge with cause-and-effect relationships is this: consider a woman who took an antidepressant during pregnancy and had a baby with a birth defect. Would her baby still have had a birth defect if she hadn’t taken the medication? We don’t have a time machine, so we can’t know.

This question is important because it’s the core of what causation means – did the medication actually make a difference? To say the medication caused the birth defect means the outcome would have been different without the medication. Since we can only observe what actually happened, not what would have happened, researchers must estimate this “what if” scenario using statistical methods, which requires teasing out and accounting for other possible causes. In this example, is it the antidepressant, the random chance of birth defects that any baby might have, or some other factor?

Causality’s gold standard: Randomized controlled trials

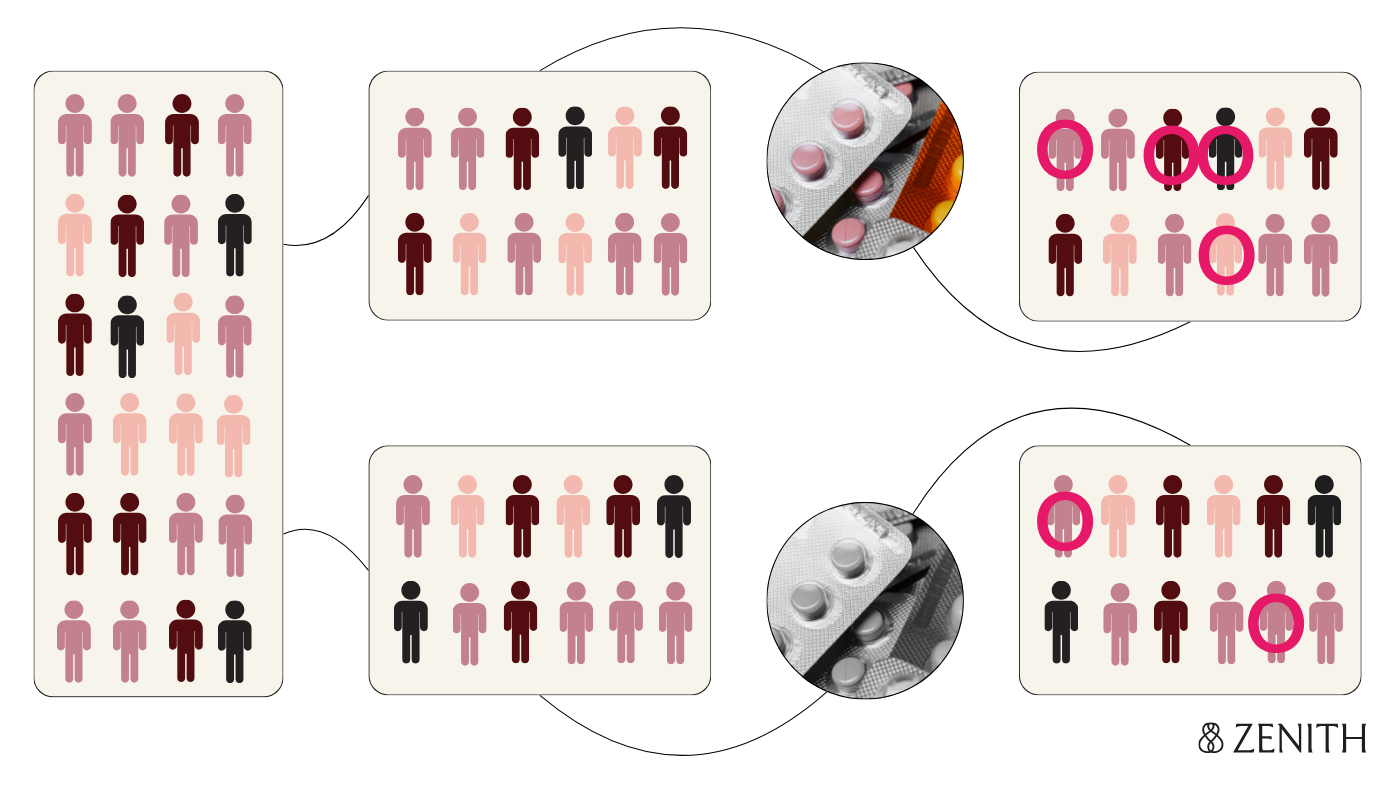

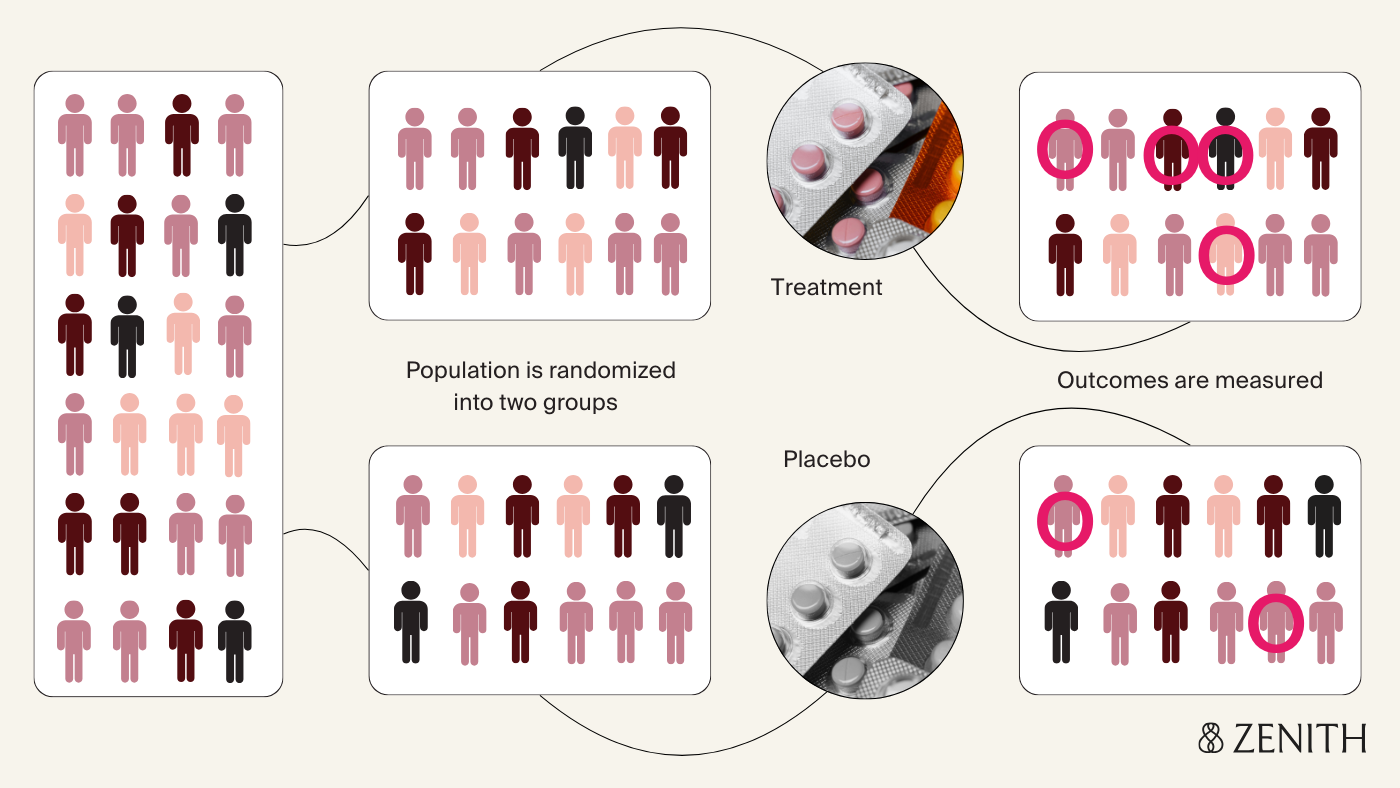

The gold standard for establishing causality is the randomized controlled trial design, or the RCT. To answer “Do antidepressants cause birth defects?”, let’s say researchers randomly assign pregnant women who are prescribed antidepressants to two groups – one receives the regular medication, and the other receives a placebo, or sugar pill with no active ingredient. Neither the researchers nor participants know who is in which group. This prevents anyone's expectations about the treatment from influencing the results.

At the end of pregnancy, researchers compare rates of birth defects in the two groups; observing higher rates in the antidepressant group suggests the medication does increase risk. The biggest strength of this design is the randomization, which ensures that participants in both groups are similar to each other with the exception of their treatment status – the fact that someone took the medication depends solely on if they were randomly assigned to, rather than other external factors that might influence how likely someone is to take the medication (which may also independently affect how likely it is for their baby to have a birth defect). This improves the ability of the study to establish a cause-and-effect relationship between the antidepressant exposure and the outcome (if it exists), and to rule out other potential explanations for observing the outcome.

When RCTs aren't possible, enter observational research

The biggest challenge with RCTs in pregnancy involves ethical considerations around consent and risk. Pregnant women are classified as a vulnerable population in research regulations, meaning their inclusion requires special protections and oversight. Concerns about potential harm to mom and baby, stemming from events like the thalidomide tragedy, have often led to pregnant women being excluded from research, creating a problematic cycle where risks remain uncertain due to lack of data.

In addition to the overall hesitance to expose both mom and baby to experimental or unproven interventions, which have the potential to cause outsized harm during pregnancy, another key ethical complexity is that research decisions involve the pregnant woman who can provide informed consent, and the fetus, who cannot. This is where observational studies become essential to build our knowledge.

Observational studies differ from RCTs in that participants are not assigned to a treatment or intervention – instead, researchers observe participants in real life, collect data, and analyze outcomes without any control over their exposures.

Observational studies can come in different flavors – in cohort studies, for example, researchers follow groups of people defined by a specific variable of interest (like a risk factor, treatment, or other intervention – e.g., children born between 2007 and 2018 in Sweden to mothers who did and didn’t receive prescribed opioids during pregnancy) over time to see who develops certain outcomes.

Case-control studies, on the other hand, work backwards, comparing the different exposures of people with and without a specific outcome (like a birth defect).

These studies can use existing data sources, or they can prospectively enroll and follow participants, collecting detailed information over time. Each design has tradeoffs between scale, cost, and data quality, and nuances in their ability to establish causality.

Correlation does not equal causation

Without randomization, it’s harder to know if any of the associations we observe are truly causal, since there are many other ways in which treated groups may differ beyond just their exposure status. Let’s say researchers now use observational data to answer the same question about antidepressants and birth defects, and find that rates of birth defects were higher in the group of women who had taken antidepressants. This shows a correlation – a relationship or association.

But, as the saying goes, correlation does not equal causation.

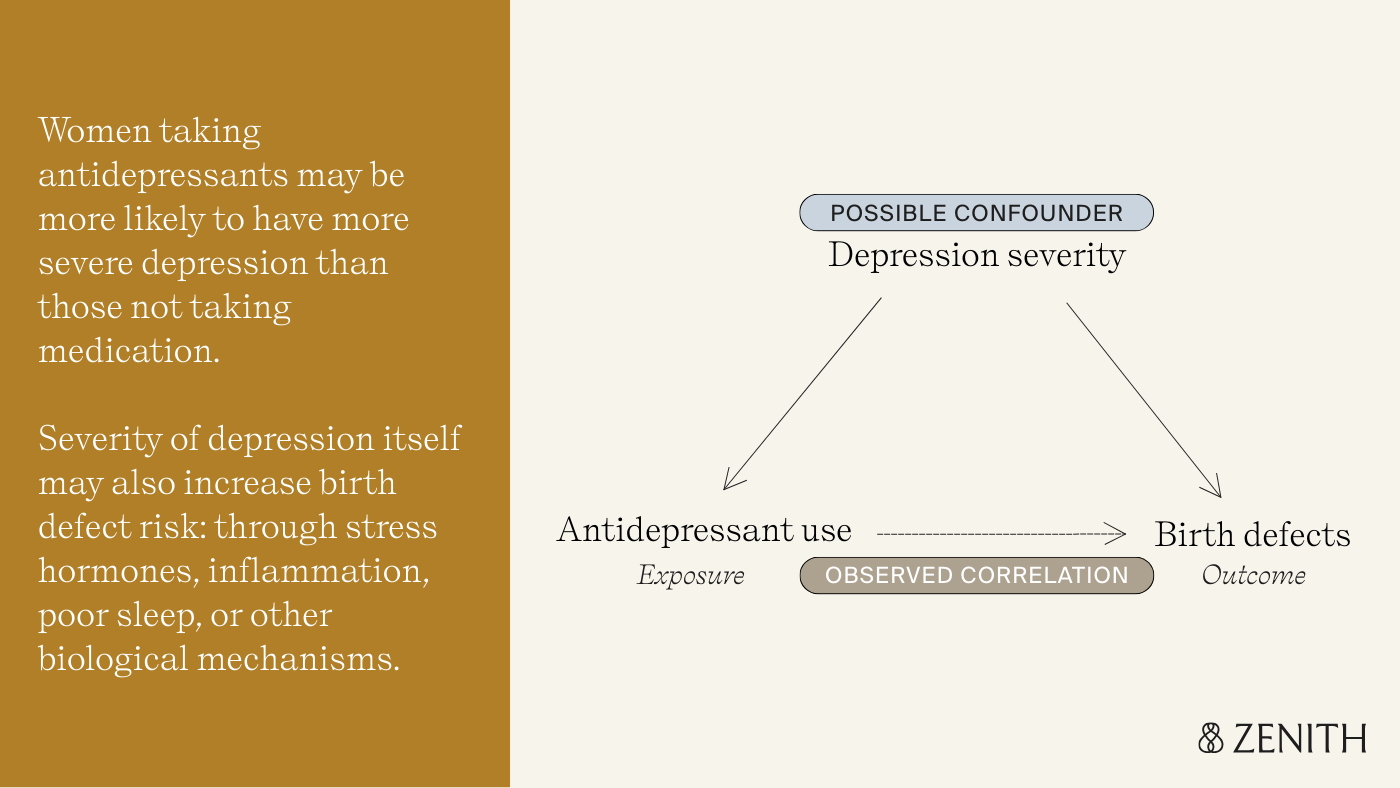

With observational studies, there could be many other explanations for why birth defect rates were higher among those who took antidepressants – in other words, variables that are the true cause of the birth defect. This concept is called confounding.

For example, women taking antidepressants are more likely to have more severe depression than those not taking medication. Depression itself, through stress hormones, inflammation, poor sleep, or other biological mechanisms, might increase birth defect risk. This makes it difficult to disentangle whether the underlying condition or the medication were the true cause of birth defects in the treated group.

How researchers get it right: design and statistical methods

This is why robust study design and appropriate statistical methods are essential to draw meaningful conclusions from observational research – not every study is created equal. Researchers can use statistical techniques to address confounding and improve the study’s validity, or its ability to accurately measure what it intends to measure.

One observational study on SSRI use and the risk of cardiac defects made the treated and untreated groups comparable based on their likelihood of being prescribed antidepressants, accounting for measured variables like sociodemographics, depression severity, and more (an approach called propensity score matching). This creates groups that are similar in important ways, mimicking what randomization does in RCTs.

Even well-designed studies face other challenges. The same study on SSRIs and cardiac defects used prescription claims data to identify which women did and did not take the SSRI. Knowing someone filled a prescription doesn’t guarantee they actually took the medication, so some women in the ‘treatment’ group may not have taken their antidepressants at all – making the groups appear more similar than they really were by essentially diluting the ‘treatment’ group, and muting the real risk identified.

This is why it’s so important that studies state their limitations – no single study can tell the whole story. To build confidence in the evidence, researchers often replicate studies, testing whether findings hold up in different populations with different data or methods. Doing so is an important part of the scientific process that holds researchers accountable and strengthens the evidence base – by confirming findings in new populations, exposing flaws, or refining existing theories.

Because a study’s conclusions are only as sound as the data and methods behind them, more studies don’t always mean stronger evidence. A poorly designed study repeated 50 times might yield the same results, but doesn’t mean that the findings are stronger just because it’s been replicated with the same sets of design flaws.

The most trustworthy findings come from research that uses the best data and methods to answer the question – which is why new research can sometimes overturn conclusions from multiple earlier studies.

This happens fairly often in pregnancy research – in a well-known example, conclusions from a recent large-scale Swedish study on acetaminophen use during pregnancy and risk of autism and other neurodevelopmental disorders using sibling comparisons (a novel study design for this question) found no evidence of a causal relationship, when multiple previous studies showed a link.

Where we go from here: A vision of evolving, evidence-based pregnancy knowledge

These challenges are part of what makes science, science. Research is an iterative process, each well-designed study helping to further refine our understanding even when individual studies can't provide definitive answers on their own. Observational research is remarkably powerful – it's how we've built most of our knowledge about medication safety in pregnancy, and it continues to be essential for answering questions that can't be studied any other way.

The more we invest into building the infrastructure to systematically collect as much high-quality data as possible on pregnancy exposures and outcomes over time, the better equipped we’ll be to transform the evidence base from fragmented individual studies into comprehensive, actionable knowledge.

Making this investment is central to our mission at Zenith: advancing maternal health for the future while empowering women with the evidence that exists today.

We've come a long way from seed-based pregnancy tests. The next leap forward is building rigorous research infrastructure, at scale, to answer the many questions that remain.